The NFL Draft is already the most absurd spectacle on television, a slurry of brands and military hardware and grim self-serious analysts solemnly intoning that a player has tremendous instincts and sideline-to-sideline speed but might not have the SIZE and LENGTH to contribute right away in the NATIONAL FOOTBALL LEAGUE, but the fact that we are all sealed in our homes during a terrifying pandemic meant that NFL was going to reach operatic heights of absurdity.

For weeks leading up to the draft, we had heard about the technical challenges. There have been stories about how GMs are converting their houses into Draft War Rooms, installing nuclear submarine defense infrastructure to their suburban mansions and complaining about the possibility of rogue cells waging Cyberwar against their zoom conference calls even though, as far as I can tell, the entire infrastructure of drafting involves being able to pick a name off a list and make a few phone calls.

The WNBA had done its draft with few hiccups a few weeks earlier, and everything had more or less worked out. The show cut between commissioner Cathy Engelbert, a small ESPN crew of analysts, draft picks in their homes, and reporter Holly Rowe interviewing them. There were a few glitches-- several draft picks had not been told to mute their televisions or use headphones so we got the classic sports radio situation of needing someone to scream "you gotta turn down your radio" at a person although these are professional athletes and not a mustache guy in the middle of proposing a baroque series of trades to reacquire Robby Gould, but watching the players at home celebrating with their families was very charming. The NFL saw this and decided to brand its version a Virtual Draft; the GM of the Detroit Lions made his IT guy live in a Winnebago outside his house in case some villainous hackers decided to break into the Lions' mainframe and gain the incredible draft intelligence that the Lions were targeting shitty football players.

The NFL draft included a solemn introduction from Roger Goodell who wanted to talk about These Uncertain Times. Goodell lives for this. He seems to see the NFL as the nexus of brands and a nebulous form of American patriotism involving tanks, and the solution to every crisis is a sluice of ads showing concern over triumphant piano music. Goodell's ideal response to a global catastrophe would be to fuse members of the military into exoskeletons made from the Official Pickup Truck of the NFL to shoot at the virus with laser guns while Domino's Pizza solemnly remembers the fallen. They started the draft with a performance of the National Anthem and then cut to a TV monitor full of people who had painted their faces to look like footballs.

Goodell, standing in a rumpus room decorated with carefully curated knickknacks, was not up to the task of whatever he was trying to accomplish. His wooden bearing reminded me of the famously cadaverous Chicago-area lawyer Peter Francis Geraci who has been haunting UHF airwaves since the mid-1980s or a hapless Vice President of Ketchups thanking the Sun Belt Conference for participating in the Amalgamated Condiments Bowl. His face was red as a sockeye salmon. He later changed into a sweater and then, on day two, managed to slip into a focus-grouped easy chair. The whole setup reminded me of one of those Sally Struthers correspondence school infomercials. The business of the draft itself remained hilariously mundane. This is because the essence of the draft remains a televised list reading. In many ways, the virtual draft served as a more normal televised event than usual because most of the insane spectacle of the draft involved packing thousands of people into a Bud Light Draft Zone where they can stand in line to do the drill where you have to run through tires with your KNEES UP DAMMIT or to don jerseys and scream at picks that they have absolutely never heard of before Goodell would come out flanked by another group of military personnel.

Some of the weirdest parts of the draft involved attempts to awkwardly recreate the live experience. Goodell invited fans to boo him via zoom. Before every pick, Goodell would bring up a small smorgasbord of teleconferenced fans in full team regalia to cheer the picks while he goaded them in a manner that can best be described as executively. The fans were barely visible and audible; even though ESPN has rebranded as the network that lets Michael Jordan

say "fuck" or even Scottie Pippen, it is not going to let some guy in an

elaborate, homemade Los Angeles Rams headpiece bellow one out on

national television in front of you, the Commissioner of the National

Football League, and God.

The other change from the draft is that it brought us inside the homes of NFL coaches and general managers and dozens of draft picks. This provided us with several shots of goatee guys in team-branded apparel doing some action packed texting in carefully-prepared draft areas where they could ostentatiously display as-told-to books by football players on Leadership or revel in Kliff Kingsbury's palatial opulence, or even cut to Mike Vrabel allowing his rowdy, mulleted sons to operate a carnival of the bizarre in the background. ESPN's analysts also set up at home except for Mel Kiper, who appeared to have transported himself into a 1990s CD-ROM game.

The business of the draft itself remained hilariously mundane. This is because the essence of the draft remains a televised list reading. In many ways, the virtual draft served as a more normal televised event than usual because most of the insane spectacle of the draft involved packing thousands of people into a Bud Light Draft Zone where they can stand in line to do the drill where you have to run through tires with your KNEES UP DAMMIT or to don jerseys and scream at picks that they have absolutely never heard of before Goodell would come out flanked by another group of military personnel.

Some of the weirdest parts of the draft involved attempts to awkwardly recreate the live experience. Goodell invited fans to boo him via zoom. Before every pick, Goodell would bring up a small smorgasbord of teleconferenced fans in full team regalia to cheer the picks while he goaded them in a manner that can best be described as executively. The fans were barely visible and audible; even though ESPN has rebranded as the network that lets Michael Jordan

say "fuck" or even Scottie Pippen, it is not going to let some guy in an

elaborate, homemade Los Angeles Rams headpiece bellow one out on

national television in front of you, the Commissioner of the National

Football League, and God.

The other change from the draft is that it brought us inside the homes of NFL coaches and general managers and dozens of draft picks. This provided us with several shots of goatee guys in team-branded apparel doing some action packed texting in carefully-prepared draft areas where they could ostentatiously display as-told-to books by football players on Leadership or revel in Kliff Kingsbury's palatial opulence, or even cut to Mike Vrabel allowing his rowdy, mulleted sons to operate a carnival of the bizarre in the background. ESPN's analysts also set up at home except for Mel Kiper, who appeared to have transported himself into a 1990s CD-ROM game.

The draft's attempt to straddle the line between bone-crunchin' football action and solemn discussions of the global pandemic and concurrent economic crash was handled in the same ridiculous and ham-handed way that the NFL handles anything but talking about football and the same ludicrous ways that corporations are maneuvering to continue selling things. Every few minutes, the draft would give way to a series of identical commercials about These Uncertain Times; the eerie repetition of that phrase and the attempts by Taco Bell to show resilient heroes grasping their taco boxes has put us all into a George Saunders short story.

The draft's attempt to straddle the line between bone-crunchin' football action and solemn discussions of the global pandemic and concurrent economic crash was handled in the same ridiculous and ham-handed way that the NFL handles anything but talking about football and the same ludicrous ways that corporations are maneuvering to continue selling things. Every few minutes, the draft would give way to a series of identical commercials about These Uncertain Times; the eerie repetition of that phrase and the attempts by Taco Bell to show resilient heroes grasping their taco boxes has put us all into a George Saunders short story.

And yet, in its own moronic way, the NFL draft did provide a useful service this weekend. Along with ESPN's Bulls documentary, the draft served as a vaguely sports adjacent thing to put onto television that millions of people would be watching and you could follow along and make dumb jokes with all of the other people who like to do the same thing on the internet, and if that meant having to endure a quavering Goodell invoking The Power of America and Specifically Football In These Uncertain Times and to watch as the Bears picked a Notre Dame Guy and no one took anyone from Northwestern then so be it.

Sports may be shut down, arenas may be empty, and the entire world might be on quarantine, but that will not stop the intrigue gears from spinning at Bulls Headquarters. One of the only meaningful pieces of sports news-- that is to say sports news divorced from the pandemic and the eternal question of when sports will start up, whether billionaire owners will deign to pay stadium support staff, and what sorts of choreographed line dances professional athletes are tik toking in their estates-- is that the Bulls, in a seemingly impossible coup, have hired a new front office. They brought in Denver GM Arturas Karnisovas as Vice President of Basketball Operations, sidelined John Paxson into a reportedly salaried position to sort of hang out, and finally hurled Gar Forman into a crevasse in the crust of the earth.

This being the Bulls, reporting has suggested that the change came from Paxson. Only on the Bulls can change come from an executive finally deciding to scheme against the only opponent strong enough to beat Paxson in a bureaucratic battle-- himself.

There have been millions of words by aggrieved Bulls fans written on the internet about the Paxson and Forman years, but while it is important to lament the various Doug McDermott trades throughout the years, I'm more drawn to the atmosphere of paranoia and dread surrounding the organization as it retreated further into a sclerotic decline that led to people screaming FIRE GARPAX at Stephen A. Smith as he attempted to interview Zach LaVine. So, here are some episodes and vignettes as a review of the Garpax era.

Randy Brown's Espionage Cell Activated to Pass Crucial Intelligence About Fred Hoiberg

"Gar has never come to me and said, 'Hey, Randy, I want you to be a spy

in Fred Hoiberg's locker room.' That doesn't even sound right. Gar and

Pax (executive vice president John Paxson) would never ask me to do

that. And Fred Hoiberg knows that." Randy Brown to the Chicago Tribune, Feb. 4, 2017.

Rumors circulated among allegations from Jimmy Butler and somehow Rip Hamilton that assistant coach and former Jordan-era Bull Randy Brown was a spy in the locker room for Gar Forman, who recruited him to play for New Mexico in the 1980s. These players accused Brown of discussing the inevitably complicated Bulls locker room politics to Forman and, we can assume, strategically hiding in lockers, using DNA from discarded towels to have facial reconstruction surgery when he needed to disguise himself as Jerian Grant, locking himself in the trunk of Robin Lopez's car in order to compile a dossier of rides he likes at Six Flags Great America, and doing "wet work" when it was necessary to destroy one of Paul Zipser's knees because he had badmouthed Forman in a German-language newspaper not understanding the reach of Forman's network on the Continent.

Many basketball teams have had fucked up, dysfunctional locker rooms. Few have approached the truly operatic feuding between various camps of players, coaches, and the omnipresent front office than the Three Alphas Era Bulls that resembled the feuding component states of the Holy Roman Empire. But there are also few teams that have had so many allegations of spying from the front office; this is not even my favorite or funniest incidence of alleged espionage from the Bulls.

Everyone involved has denied these allegations, but I just want anyone reading this to think about Gar Forman, dressed like a German walk signal, silently passing papers to undercover basketball operatives at the United Center-adjacent Billy Goat Tavern while saying cryptic passwords like "it feels like spring so often for one week in February" that tell the person to compile a detailed report on whether Fred Hoiberg is getting through to Denzel Valentine.

Bulls Players Open Roaring, Grunting, Shaking Shipping Crate, Unleash Jim Boylen

The Bulls fired Fred Hoiberg and then, arriving from a secure basketball coaching facility, was a flesh-skulled maniac wailing and gnashing its teeth and demanding wind sprints. Boylen had been on Hoiberg's staff and had won a championship as one of Gregg Popovich's assistants, but I don't think anyone had seen this coming, this surreal mutant gym teacher taking over the Bulls and immediately wreaking so much havoc that the players needed to form a bureaucratic structure for Corporate Governance in an attempt to shield themselves from him.

Jim Boylen has to be one of the funniest coaches in NBA history. I have often written about sports coaching as a position bereft of dignity-- it is difficult for someone to become a gris eminence when there are hundreds of hours of footage of that person screaming at officials, throwing clipboards, sniping at beat reporters, and sweating through the suits that they have to wear for some reason; the price that coaches pay for exorbitant salaries and fame is that they are some of the few people whose apoplexy gets captured repeatedly by cameras, and they also are constantly subjected to having Stan from Glen Elyn call into sports talk radio every day and talk about how incompetent they are while trying not to get into an accident on the Eisenhower Expressway. But Boylen has done himself no favors-- he comes across as an oaf, a boob, a strange maniac who regardless of his knowledge about basketball has seemed to also be a person who has no idea how to connect with people, handle the press, or exist in a human society that is not solving problems with through a ritual combat by dodgeball.

That's when the attack comes SWISH from the sides from the two

other Jim Boylens you didn't even know were there

That's when the attack comes SWISH from the sides from the two

other Jim Boylens you didn't even know were there

The uncertainty around the NBA and sports leagues in general in the

midst of this pandemic has made Boylen's job status unclear. There

might not be a point to firing a coach while there are no games being

played and while his job duties are probably teleconferencing with

players with his bulbous head filling up a zoom window while screaming

at them about how he's "jacked up" to see them doing pushups on

Instagram or whatever. But we can assume that Boylen cannot be long for

the Bulls and while hiring a more competent and palatable maniac will

be better for the team, we will all be losing out on his press conferences, bizarre quotes, and his weird and infuriating time outs at the end of games the Bulls have no chance of winning that have nearly caused altercations.

The Bulls also in the past had also elevated an interim coach named "Jim Boylan" who was an entirely different person and this has nothing to do with the previous paragraphs but it blows my mind every time I think about it.

The Bulls Send Luol Deng for a Recreational Spinal Tap

Sports fans have a tendency to blame their team's medical staffs for rashes of injuries, and this is not always fair. Most fans are not physicians or professional sports trainers and have no idea what teams are or are not doing to prevent and treat injuries. Many injuries are the result of the fact that sports asks athletes to make insane and unnatural demands on their bodies and, in basketball, players are constantly jumping, landing, and getting bashed in the sternum by either Dale or Antonio Davis.

But in some cases team's medical staffs can make mistakes that are clear and disastrous, and that would be the time that the Chicago Bulls sent Luol Deng to get an unnecessary spinal tap that could have killed him in 2013. Deng had been complaining about flu-like symptoms. Bulls doctors diagnosed him with meningitis and sent him to the hospital for the procedure, which developed complications including leaking spinal fluid. Deng lost fifteen pounds in a few days and was beset with intense headaches. The Bulls listed him as out with "flu-like symptoms."

No one here is arguing that the Bulls deliberately sent Deng into a dangerous medical situation but the Bulls front office touch was to do so in the midst of an atmosphere of downplaying injuries and illnesses. Here is how one anonymous Bulls staffer put it in a scouting report quoted in this ESPN article from 2013:

Luol called me and told me he was really sick and had to go to the

hospital. This was when we were in Miami in the playoffs ... soon after I

get off the phone with Luol (redacted) play, that he's on his way to

Miami. I told Thibs there is no way, he's on his way to the hospital, it

was a bad situation. He blamed the team and they put pressure on him to

play when he was seriously sick.

The article also mentions the entire incident happened in the context of the Bulls pressuring Deng to put off surgery to an injured wrist in the previous season. The entire thing also happened in the maelstrom of the front office's neverending war with Derrick Rose over whether or not he was ready to come back from his various catastrophic knee injuries that had reached a boiling point that spring, when the Bulls believed Rose was ready to return and Rose decided to miss the rest of the season. The Bulls and Rose feuded in the newspapers for awhile, and the relationship between the team and Rose soured while Bulls players questioned the organization's commitment to their health or grinding away to heroic second-round playoff exits.

Tom Thibodeau's Staff Enacts the Moscow Rules

The thing I most appreciate about the GarPax area is their dedication to general Cold War tradecraft. NBA teams have traditional folkways of dysfunction: feuding with players, undermining coaches in the press, or even exploring the avant garde ends of dysfunction like the time Mark Jackson attempted a bizarre process of psychologically torturing Festus Ezeli. The Bulls, though, made this into an art. The Bulls were running agents and, in my favorite GarPax allegation originally made by Adrian Wojnarowski, bugging offices. Woj claimed that Bulls personnel were employing the classic tactic of running electric fans as white noise because they feared that Forman was listening to their phone conversations.

I should note that there is no evidence that anyone bugged the offices. There is also no evidence that Gar Forman drove a van marked Bannockburn Utility Landscape and Lawn Sculpture around the practice facility for surveillance purposes or cut off trade talks saying "not now I'm in the van." No allegations have at this time surfaced of Bulls players using yellow chalk in a telling location over Kirk Hinrich's garage to announce a secret meeting or attempts to spirit away Ron Adams over the Glienicke bridge.

John Paxson Tries to Murder Vinny Del Negro Over Joakim Noah's Minutes

The delicate interplay of player usage, injuries, and toughness has become a hot-button issue in the NBA in recent years as teams have increasingly rested players, come up with a semi-scientific term that Sloan Sports people can use so they can say "load management" and pretend that it's an Analytic, and given Jeff Van Gundy something else to complain about, but nowhere in basketball did that play out as dramatically as the time that John Paxson attempted to shove his hand through Vinny Del Negro's chest in an argument about whether Joakim Noah was playing too many minutes.

Paxson has enjoyed recreationally feuding with his coaches. Though he generally seems to prefer sniping at them in the press, undermining them, and then hiring a new one based on his criteria that all coaches must follow the eternal cycle of a Hair Guy giving way to a Bald Asshole, in this case he decided to showcase his Aggressive Shove Style of martial art. Paxson then had Bulls assistants wheel out a table full of weapons while he gave Del Negro the option to either do a knife fight with their wrists tied together like in the Michael Jackson Beat It video or to dip their fists in glue and then in shards of glass before fighting to the death on the roof the Berto Center.

Instead, Paxson holstered his fists and bided his time for a few weeks to fire Del Negro. Within a couple seasons, he would be in an open war with Thibodeau, would fire his replacement Fred Hoiberg within a few seasons, and then hire Jim Boylen, an inept doofus who is the laughingstock of the NBA and whom Paxson seems to love. Perhaps Boylen has already defeated him in combat.

ESPN will be airing a 10-hour documentary about the 1997-8 Bulls, another organization that was riven with dysfunction, conflict, and revolt among the front office, the players, and the coaching staff. But in this case the conflicts came from a team that spent the 1990s as one of the most dominant teams at anything in my life; the conflict served as a dramatic undercurrent to all of the winning, destroying Karl Malone, Jordan referring to his centers as "twenty-one feet of shit," etc. During the GarPax era, the Bulls got a few really good teams and a lot of years where the most compelling thing about the Bulls was the deranged bureaucratic infighting.

The

Major Leagues will not be generating any new baseball for some time,

which makes this an appropriate time to dip into Important Baseball Lore.

The most indispensable baseball writing this offseason for me as been Joe Posnanski's Baseball 100,

where he rates his top 100 baseball players of all time and writes

essays about each one, and I thought I should shamefully rip that off.

So here's the BYCTOM 100*, a series of essays not on the top 100

baseball players of all time, but of lesser heralded players that have

floated through the ether of baseball, the players that David Roth

refers to as Guys, the foundation of baseball itself that the giants of

the sport can homer off of, do handshakes with, and occasionally get

humiliated by because baseball is a weird and cruel game. The asterisk

is of course because there is no way I will do 100 of these, let's face

it I'll be shocked if I do five. If you have a suggestion for someone

to be covered in BYCTOM 100*, please send it to me, and I'll consider

it.

MICAH OWINGS

There is nothing that Rob Manfred likes more than going out onto the parapet of his Baseball Tower and issuing arbitrary rules edicts meant to chip away at the his apparent belief that people despise baseball and he must save it by mandating how teams use relief pitchers. Under Manfred, the designated hitter is almost certain to disappear from the National League; with his propensity for proclaiming rules changes with almost no warning, the DH may actually have already gone and he has simply not gotten around to telling us yet because he is trying to figure out how to restart baseball in a series of Arizona Virus-Dome compounds that will eventually go dark and reemerge with Manfred proclaiming himself a prophet or deity while wearing an interesting robe.

No baseball rules debate has become more pointless and tedious than the eternal war over the designated hitter, and I have no wish to relitigate that battle. Most people prefer the style their team plays and that they are used to, and anything beyond that is an aesthetic choice. It is true that as a whole, most pitcher plate appearances amount to complete wastes of time, as close to an automatic out as exists in baseball, and the ability to predict the end of a rally because of pitcher is due up is one of baseball's most infuriating impending doom scenarios. At the same time, the rare times a pitcher does anything at the plate constitute the most memorable and joyful experiences in baseball, and there are still fewer more enjoyable baseball archetypes for me than the pitcher who can hit a little.

The patron saint of hitting pitchers is Wes Ferrell who spent the 1930s as a good pitcher for Cleveland who also knocked the hell out of the ball. In 1935 alone, he led the American League with 25 wins and also batted .347/.427/.533 with seven home runs. According to this exquisite Wikipedia Sentence "He was a fiery competitor and a brilliant player with natural talent,

whose achievements may have been obscured by his irascibility."

My favorite pitcher who can hit a little is Carlos Zambrano, who was somehow a switch hitter good for a least a dinger or two a season and one egregiously reckless adventure on the basepaths. Zambrano also fought teammates, pitched a no-hitter as the road team in Milwaukee against an Astros team forced to flee from a hurricane, and once screamed at journalists "This is not a baby's game! This is a man's game!"when asked why he was repeatedly throwing at Jim Edmonds.

But the most emblematic pitcher who can hit a little from this era remains Micah Owings. Owings, a prodigious high school slugger, flourished as a two-way phenomenon in college. After two excellent years at Georgia Tech, he transferred to Tulane and achieved another level as a powerhouse pitcher and outfielder, hitting .355/.470/.719, and also going 12-4 with 3.26 ERA. Arizona took him in the third round as a pitcher, but when he came up in 2007, he appeared as a shimmering vision of a pitcher who can obliterate the baseball.

Here's a brief aside on pitchers hitting. In 2007, Owings's debut season, pitchers came to the plate 5,899 times and managed to eke out a cumulative .146/.177/.188 line. This is a baseball obscenity; pitchers appear to have been coming up to hit wielding novelty souvenir bats that say "save big money at menard's" or giant foam number one fingers. Very few position players have ever approached this anemic standard. I searched Baseball Reference to find players with an OPS lower than .365 who played a decent chunk of the season (at least 200 plate appearances), and found that the champion of all of them was a catcher for the Brooklyn Superbas (at that point only colloquially known as the "Trolley Dodgers" along with a host of other nicknames including the Bridegrooms, the Atlantics, and Ward's Wonders that all seem have been used interchangeably) who managed it five times in the deadball era. The last contemporary person to do it was the former all-star Dodgers shortstop Maury Wills as a 39 year-old running on fumes and managing an OPS+ of 3 in 1972.

(Wills resurfaced in the early 80s as the hilariously disastrous manager of the Seattle Managers who infamously tried to extend the batter's boxes an extra foot hoping no one would notice. His Wikipedia entry notes that Oakland manager Billy Martin saw it and alerted umpire Bill Kunkel. The Wikipedia entry contains the extraordinary phrase "under questioning from Kunkel, the groundskeeper admitted." Wills features prominently in this wonderful Mariners documentary.)

Micah Ownings came up 64 times in his rookie season in 2007, hit .333/.349/.683, clubbed four dingers, smacked seven doubles and a triple, and led all pitchers with an OPS of 1.033. That is the third-best by a pitcher (with at least 50 PAs) ever; only Wes Ferrell and fellow two-way threat Don Newcombe topped him, although they both did that with nearly twice as many plate appearances, which is even more impressive. He hit two home runs in one game as part of a four-hit night, claiming a record eleven total bases. Owings also was a decent pitcher that year, compiling a 111 ERA+, and he attracted a mild fanfare, the type that causes baseball announcers to say "you have to be careful with Owings here, we know this guy can swing the bat."

Owings's stats took a dip in both hitting and pitching his next year (he still hit .304, but the power was not there), and the Diamondbacks traded him to Cincinnati as a throw-in as part of a transaction involving Adam Dunn. He rebounded for the Reds at the plate in 2009. That year, he hit an OPS of .818 with three dingers, but inexplicably lost the Silver Slugger to Carlos Zambrano who hit worse than him in almost every category but was a much better pitcher and higher-profile star. That was pretty much it for Owings as a starter. He began coming out of the pen in 2010, and his plate appearances cratered-- the Red used him as a pinch hitter a few times, but he was not nearly as effective, his pitching never regained the promising form, and he bounced around the minors and independent leagues for awhile, attempting to pitch but increasingly appearing as an outfielder.

The statistics with any pitcher hitting in the current era remain strange because they appear so infrequently. Owings has since been eclipsed by two-way superstar Shohei Ohtani, who, at least until an injury derailed his pitching career, looked like he could become baseball's greatest two-way star since Babe Ruth. And baseball usually has at least one or two guys floating around who pitch a little and hit a little and do neither particularly well but are noteworthy for that. The emblematic star of this role for me remains the immortal Brooks Kieschnick, and the Reds currently have a pitcher and anthropomorphic bicep named Michael Lorenzen on their roster who sometimes moonlights as an outfielder.

But Owings is emblematic of the ineffable romance of pitchers hitting, of pitchers doing anything other than walking up to the plate and immediately back to the dugout, of pitchers occasionally causing a tingle of fear in their opposites from other teams, and of the perfect aesthetics of them somehow managing a hit and then standing awkwardly on the basepaths in their dorky satin jackets, these masters of baseball who have played the game their entire lives only to arrive at the sport's pinnacle that few can even dream of and still look profoundly uncomfortable with one of baseball's most basic tasks.

The

Major Leagues will not be generating any new baseball for some time,

which makes this an appropriate time to dip into Important Baseball Lore.

The most indispensable baseball writing this offseason for me as been Joe Posnanski's Baseball 100,

where he rates his top 100 baseball players of all time and writes

essays about each one, and I thought I should shamefully rip that off.

So here's the BYCTOM 100*, a series of essays not on the top 100

baseball players of all time, but of lesser heralded players that have

floated through the ether of baseball, the players that David Roth

refers to as Guys, the foundation of baseball itself that the giants of

the sport can homer off of, do handshakes with, and occasionally get

humiliated by because baseball is a weird and cruel game. The asterisk

is of course because there is no way I will do 100 of these, let's face

it I'll be shocked if I do five. If you have a suggestion for someone

to be covered in BYCTOM 100*, please send it to me, and I'll consider

it.

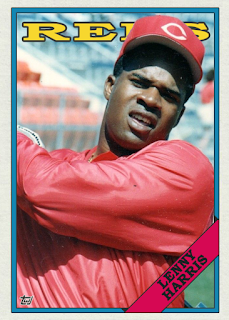

LENNY HARRIS

Lenny Harris's Baseball Reference page lists his position as Pinch Hitter. He is also a third baseman and outfielder, but those served as minor distractions on his path to becoming baseball's Pinch Hit King. Over eighteen seasons in the major leagues, Harris amassed 212 pinch hits, blasting by former record holder Manny Mota's 149. The only person in the same galaxy as Harris pinch-hitting wise is Mark Sweeney, who got 175. No current player comes close; the only active players to even breach 50 are Matt Joyce, Matt Adams, and Daniel Descalso, whose last season in Chicago was so riven with hitting ineptitude that appeared to be trying to get the ball out of the infield by way of strongly-worded letters. Harris stands along as a giant of the bench, the Sultan of Sit, and after a few hours of poking around the internet I'm convinced that he has achieved one of the strangest and least-replicable baseball careers possible.

The most remarkable thing about Lenny Harris's time as the Dean of Left-Handed Bench Bats is that his hitting statistics are just south of mediocre. He's a career .269/.318/.349 hitter. Most of his best hitting years came as a young, everyday infielder for the Dodgers; in his ideal form as a pinch hitter he hit an anemic .264/.317/.337. He did not walk a ton and, for a stocky lefty off the bench, he offered almost no power, never managing more than five home runs in a season. Baseball Reference credits him with just 1.7 WAR for his entire eighteen-year career. Sweeney was a much better hitter, and rowdy Baseball Uncle Matt Stairs leads the majors with 23 pinch hit dingers. Harris only leads in the category of hits and plate appearances as managers kept summoning Harris to pinch hit ineffectively over and over again.

The mystery for me is how Lenny Harris managed to stick around for eighteen years as a bench bat barely able to breach the .700 OPS threshold. Because Harris played most of his career in the 1990s and early 2000s, my natural inclination was to ignore even the basic slash metrics and take a look at the triple crown stats that ruled the game then. He did not sock many homers or pile up RBIs even for the relatively few plate appearances he got over a season nor did he swipe many bases. Harris did hit the magical .300 batting average threshold several times; it is possible that his .300 seasons were spaced perfectly for him to scuffle around 2.70 or even plummet to .235, but then pull off a .300 season at the opportune time for a grizzled Moneyball villain front office person made entirely of used mouth tobacco to get on the phone and start screaming profanities at someone to sign him before mailing Bill James a manila envelope filled with violently torn up spreadsheets.

But I believe there is some sort of ineffable, spiritual purity to Harris's reputation as the preeminent pinch hitter in baseball history that transcends his underwhelming numbers. First of all, anyone who makes a living as a pinch hitter will not be exploding with OPSes because if they did, they wouldn't be pinch hitting. But more importantly, Harris embraced pinch hitting and made it into an arcane art-- not every player can deal mentally with sitting in a disgusting dugout day after day eventually summoned for one at bat, but Harris mastered it, learned the Way of the Bench, and honed an approach to allow him to pinch hit dozens of times a season. This approach helped sustain Harris's career because, once you become the Pinch Hit Guy, baseball's organizational inertia means that any time a team needed a left-handed bench bat, there is no way their imagination would extend past The Guy Who Pinch Hits.

Harris had a great part of a season off the bench for the National League Champion Mets in 2000, but I first became aware of him when he signed with the Cubs in 2003. He had come off one of his best seasons the year before with the Brewers, but was miserable with the Cubs and let go when they acquired Randall Simon as part of the lopsided trade that also brought Kenny Lofton and Aramis Ramirez to the North Side. Simon is best known for an incident earlier that season when he was up in Milwaukee and decided to playfully bop one of the racing sausages in the head with a bat; this knocked the sausage down, scuffed up the person inside the costume, and caused an outcry in Milwaukee because it turns out that hitting a racing sausage in the head with a bat looks a lot like hitting someone in the head with a bat. The police got involved. Simon was still on the Pirates then, but then he got to the Cubs and had to go up to Milwaukee again and face a seething, hostile crowd desperate to avenge his unthinkable attack on an anthropomorphic bratwurst, but Simon cannily defused the situation by buying brats for an entire section and sending the person inside the costume on a free trip to Curacao.

Harris ended up joining the Marlins and facing the Cubs in the ill-fated NLCS. It would have been poetic if it was Harris who managed to hit that foul ball into the low left field stands over the bullpen or even managed a hit or walk to prolong the Cubs' agonizing death inning, but Lenny Harris's Revenge Series unfolded with l'esprit de l'escalie. He managed three plate appearances early in the series, two outs and a walk; he made the last out in a 12-3 loss. But I don't think Harris cares about any of that at all because a week later he became a World Champion.

In 1998, Lenny Harris made a pitching appearance with his Reds down 16-3 to the San Francisco giants in the ninth inning and struck out Brent Mayne looking.

The thing that I've found most compelling about Harris's career is that he sustained it for such a long time on a razor's edge. After a few years in the majors, he never again worked his way into a full-time starter but never collapsed enough to be sent to the minors. No matter what he did at the plate, when the balls were finding gaps in the infield or he was rolling over to the second baseman, some team always wanted Lenny Harris. And Harris did all of this in the strangest way possible, as a low-power contact hitter playing almost his entire career at a time when the game was teeming with available neck vein guys who were capable of anonymously blasting baseballs into low Earth orbit.

I would be surprised to see another player like Harris again. The idea of a player with Harris's skill set hanging around the major leagues for the better part of two decades seems remote at a time when teams have become obsessed with jettisoning veterans for cheaper young players; though Harris never signed a big contract, it seems that veterans like Harris are less welcome in the game than ever, especially in a baseball environment tending towards the three true outcomes instead of doing whatever he can to put the ball in play (Harris almost never struck out).

Lenny Harris was not the most productive or effective pinch hitter in baseball history. He was instead the most pinch hitter, the man called upon more than anyone in the history of the game in the pinch, a person who sustained himself in baseball for long enough to turn pinch hitting into his own arcane art, and that is more impressive.