For my money, the most enjoyable cheating scandal in any sport is when a professional cyclist is caught using a motor secreted into a bicycle. That is an incredibly brazen way to cheat. It is cartoon cheating-- the only thing more dastardly than competing in a cycling race with a literal motor would be to see someone attempt to qualify for the Olympic high jump wearing enormous springs before getting carted out of the stadium with an injury where they are folded up into an accordion shape.

Cyclists have decided to refer to this, the practice of entering a bicycle race with a literal motor attached to the bike, as moto-doping. Presumably this name comes from the more common method of cheating in bicycle races through drug regimens or those programs where Tour de France riders have all of their blood drained and clumsily replaced with a mutant ooze in a dank hotel room. This is wonderful. Somehow, a plague of guys zipping past the peloton on improvised mopeds has yielded an all-time great cheating suffix, one that should be adopted immediately by every sporting concern.

Baseball, for example, spent most of the 2019-20 offseason entangled in the Astros sign-stealing garbage can banging scandal, which by all rights should be referred to as Can-Doping. Now, the biggest story in baseball is about pitchers using exotic adhesives to doctor the baseball. It seems like the baseball world is grappling with what to call this transgression. The most common term I have seen is a crackdown on “sticky stuff;” if MLB and baseball media had any sense or clarity of purpose, they would immediately begin referring to this crisis as Glue-Doping.

Pitchers have been rubbing baseballs with foreign substances as long as the sport has existed. The current glue predicament, like most modern baseball scandals, seems to have mutated into a crisis from the twin hobgoblins of analytics and technology. Baseball undergoes an approximate five-year cycle where a new term appears on the nerdiest baseball blogs that explains an advantage or long-sought market inefficiency and then the term then filters into the Sloan Analytics circuit and front office guys wearing those Investment Vests and then finally comes dribbling awkwardly out of the of mouths of grizzled former players on studio shows and local broadcasts like a trickle of tobacco juice. One of those recent trendy metrics has been Spin Rate, which has become ubiquitous.

The consequences of the new spin rate obsession were obvious: pitchers recognized that increasing their spin rate would lead to higher paychecks for established pitchers or the possibility of a steady job in the majors for the dozens of interchangeable relievers who are belt-fed at hitters and often yo-yoed between the big club and minors.

The emphasis on spin rate manifested from technological change in two ways. First, spin rate was not something that could be measured without the fancy cameras that teams have all recently adopted as part of their increasingly-ubiquitous pitch labs. Second, pitches gained access to new sticky substances beyond the pine tar that Michael Pineda was attempting to hide by pretending it was some sort of alarming neck secretion or the various sandpapers and jalapeño snots that pitchers had used before. The most infamous of these is a product called Spider Tack, invented by one of those strongman guys who you see on ESPN2 wearing the car suspenders when strapped to a Volkswagen who made the glue so he could get a better grip on those gigantic concrete spheres that the strongman haul around. This substance was so sticky that the guy who invented it ripped his biceps because he physically could not release a boulder, and now it is used to make a guy swing and miss at a curve ball and yell an obscenity.

After reading the article on Spider Tack the thing that immediately struck me is there is no way that oafish baseball players who regularly hurt themselves in the most improbable and clumsy ways even if most of those stories are probably dopey inventions to cover for being drunk should be allowed to handle a substance that sticky. It is a minor miracle that a baseball player has not dangerously glued himself to his own person, a teammate, or a moving vehicle. I am shocked that a pitcher as not yet thrown a ball but remained stuck to it so he flies towards the mound still gripping the ball and the hitter hits it now the momentum has him flying toward the outfield still stuck to the baseball where a quick-thinking outfielder must snare him with a gigantic net before there is a five hour video review that ends with the umpire declaring that everything that happened is legal and then must flee the stadium in a bullpen car shaped like a baseball glove.

While it is obvious that the Glue-Doping crisis is real and a detriment to a game already perilously tiled towards the pitcher, I am also somewhat skeptical of the impending crackdown only because I have no faith that Rob Manfred can competently resolve this situation, especially if it empowers Cowboy Joe West to do his Buford T. Justice routine as he becomes a Forensic Ball Inspector. Or maybe they will be able to pull it off and the change is enough to give hitters a bit more juice, let the ball go into play a bit more, and make baseball more than a festival of strikeouts. Either way, I think I have been very clear that the most important thing is that the practice of doctoring balls should be known as “Glue-Doping.”

THE DINK AND THE BATH

“Those reformers tried to blow up th’ place an’ look what they got for it. The Tribune thought people was gonna stay away. Well, look at it! All th’ business houses are here, all th’ big people. All my friends are out. Chicago ain’t no sissy town!”

Thus spoke Mike “Hinky Dink” Kenna, one of Chicago’s alderman for the first ward about a notoriously debauched 1907 First Ward Ball that he put on with his fellow alderman “Bathhouse” John Coughlin. The two were a classic team-- Bathhouse John (AKA “The Bath”), a large garrulous back-slapper who came up as a massage rubber in the swanky Palmer House, and Hinky Dink, the diminutive tight-lipped schemer who served as the brains behind the illegal voting strategies that kept them in power and in illicit profits for decades. I have written about them on this site earlier, but not after reading the full treatment of their antics from Lloyd Wendt and Herman Kogan’s Lords of the Levee published in 1943 that covers the full scope of their schemes in the rough-and-tumble politics of turn-of-the-century Chicago.

Wendt and Kogan were newspaper reporters, Wendt mainly for the Tribune and Kogan for the Sun-Times, and their depiction of Coughlin, Kenna, and Chicago politics comes off as cynical amusement. There are more recent and more academic studies that effectively grapple with the effects of Chicago’s crime and political corruption during this time period, but those studies would not have the alternate title of Bosses in Lusty Chicago that this book bore for several reprintings. Wendt and Kogan instinctively know that when someone reads a book about Chicago politics in the 1890s they want to know about crooks with dumb nicknames, big mustaches, and their hands in as many pockets as possible. Much like Gem of the Prairie, a Chicago crime opus published in 1940 that I wrote about in 2018, the central question driving this book seems to be “can you believe this shit.”

Bathhouse John and Hinky Dink sampled from a wide buffet of crimes including using the police to create protection rackets for saloons and brothels in the notorious Levee district, requiring anyone who wanted a contract with the city to buy insurance from Coughlin’s firm, and other sorts of standard Chicago clout-wielding, but they reveled in the art of the boodle. Boodling, in the parlance of the time, meant giving contracts to utility companies-- gas companies, for example, or those building the then-nascent elevated trains-- only after allowing company lobbyists to brazenly bribe them. The schemes were shameless, and the contracts usually meant a bad deal for taxpayers. Given the expansion of Chicago and the burst of new technology into cities like L trains and electricity, Bathhouse John, Hink Dink Kenna, and the bevy of corrupt city officials essentially sold off the entire city’s burgeoning modern infrastructure to shell companies that often times did not yet exist or were already despised, such as one gas company whose shoddy equipment killed numerous people.

The two aldermen repeatedly faced off with reformers desperate to drive out corruption, crime, and vice. These reformers, like most late nineteenth- and early twentieth-century people devoted to good government, were blind to problems their solutions could cause and generally priggish, but it is hard to fault them on their basic premise that elected aldermen should not gleefully steal money from everybody. Wendt and Kogan, though, are not really interested in analyzing the reform agenda. They generally treat these reformers as if they were stern foils for the Three Stooges who are constantly getting their eyebrows singed off or getting hit by an errant pie meant for another Stooge. They are characters getting in the way of Bathhouse John and Hinky Dink but ultimately falling victim to their genuine popularity in the ward combined with Hinky Dink’s unstoppable voting strategy of rounding up as many indigent men as he could and registering them to vote and then hiring some street toughs to throw people down staircases and punch them using those nineteenth-century boxing stances; neither one ever lost an aldermanic election.

Of the two, Bathhouse John was the more colorful figure. He loved giving speeches constructed from the remnants of malapropisms; Wendt and Kogan also enjoy rendering his speeches in a phonetic Chicago accent that pushes the limit of typed nasalness. Unlike Hinky Dink, who preferred to scheme in his dank saloon, Bathhouse John craved the limelight like someone in collapsed cave digging towards brightness. In 1900, the Bath produced a sentimental poem he had written called “Dear Midnight of Love” that he had set to music and unveiled at the opera house. He attempted to get a famed opera diva to sing it but was rebuffed (she snorted as Wendt and Kogan note, "according to contemporary accounts"). Instead, he hired a cronie's thirteen-year-old daughter and augmented her performance with a brass band and a chorus 50 voices strong. The swells and papers ridiculed him for the spectacle, but he sold out five shows. “That settles it,” proclaimed the Chicago Daily Journal, “From now on it’s Bathos John.”

Dear Midnight of Love

Why did we meet?

Dear Midnight of Love

Your face is so sweet

Pure as the angels above

Surely again we shall speak

Loving only as doves,

Dear Midnight of Love.

Bathhouse John also bought a large property in Colorado and tried to build it into an amusement park and zoo that involved essentially stealing an elephant from the Lincoln Park Zoo.

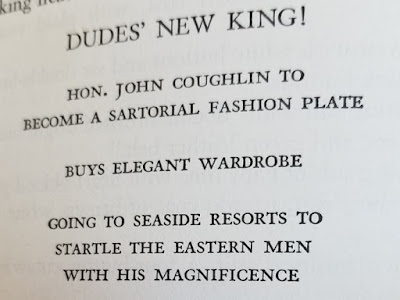

But the place where Bathhouse John made his greatest mark was in fashion. He decided that he should set a new standard for menswear that involved loud, blasting colors. Then, just before the Democratic National Convention in 1900, the Bath went out east to show off his new duds, as the Times Herald put it, “going to seaside resorts to startle the eastern men with is magnificence.” In reality, he was going to meet with Democratic power brokers before the convention to try to drum up support for Chicago mayor Carter Harrison Jr. His most notable article was a green suit described by one First Ward apparatchik as “like an Evanston lawn kissed by an early dew." The Times-Herald continued that “the alderman of the First Ward will dim the glory of J, Waldere Kirk and snatch from the latter’s grasp the crown of fame which he has worn so many seasons as King of the Dudes.”

I had made a grave and naive assumption that the King of the Dudes that the Times-Herald mentioned was Evander Berry Wall whom I had previously run across in this blog and has survived the twenty-first century with the great honor of being the Dude that pops up when you put King of the Dudes into Wikipedia. But it turns out that heavy and presumably ostentatious lies the crown, and by 1900 Evander Berry Wall was no longer King of the Dudes, presumably put out to some Dude pasture by larger and dandier Dudes. J. Waldere Kirk has become a more obscure figure here in 2021, but I was able to uncover an incredible article in the New York Journal and Advertiser from 1897 about him entitled “A Dude from Denver Reviews the Dudes of New York.”

“A dandy-dude from altitudinous Denver descended upon the Metropolis a week ago,” the article begins. “He resents vigorously the insinuation that he bears even a remote resemblance to a dude, but modestly declares that he is “considerable of a sartorial sirocco.” The rest of the article, which is lavishly illustrated with Kirk staring through opera glasses at a procession of Dudes under the legend “The Dude from West Inspects the Dudes from the East” is an interview where Kirk expounds on his various theories of wardrobes, and is one of my favorite specimens of writing where some obnoxious windbag gets to explain how things are. If there was a climactic Dude Off between Kirk and Bathhouse John where they put on elaborate hats and colorful cloaks at each other until one of them exploded into a mushroom cloud of fabric, Wendt and Kogan did not say.

Wendt and Kogan pick up the pace considerably as Batthouse John and Hinky Dink age into grises-eminences of the City Council. By the 1920s, their own political power base gets subsumed by a more violent and brazenly criminal organization: the mob under Al Capone. Bathhouse John and Hinky Dink supported Capone out of self-preservation and greed-- Hinky Dink served as an informal advisor to Capone’s chief henchman Frank Nitti while Bathhouse John hung onto his seat on the City Council, known mainly for his wardrobe and poems that were ghostwritten by a newspaper editor. Hinky Dink even managed to get elected once again as alderman at the age of nearly 80 because the Capone Outfit needed someone reliable. He was still alive when Lords of the Levee was published.

It is a bit jarring to read a book on municipal corruption where the authors seem to celebrate it. There is no doubt that Chicago would have been better off if Bathhouse John and Hinky Dink had lost power or faced any sort of consequences for their larcenous ways, but Wendt and Kogan have the reader instead marveling at their brazen schemes and Bathhouse John’s ostentatious oafishness. Readers almost can't help rooting for these characters to steal another election, humiliate another reformer or anti-vice crusader, and defeat their equally sleazy aldermanic rivals for the biggest slices of the boodle pie. As reporters, Wendt and Kogan are primarily interested in a story, and this is a great story. And, they have made a tremendous case that when a aldermen in the present day is caught using the same techniques to extort a Burger King or collect kickbacks from a gambling operation, the least they could do is wear ridiculous outfits, build a disastrous zoo, or produce a musical extravaganza.